Values groups and voting behaviour in the 2019-2024 parliament

A very brief look at how values groups changed preferences

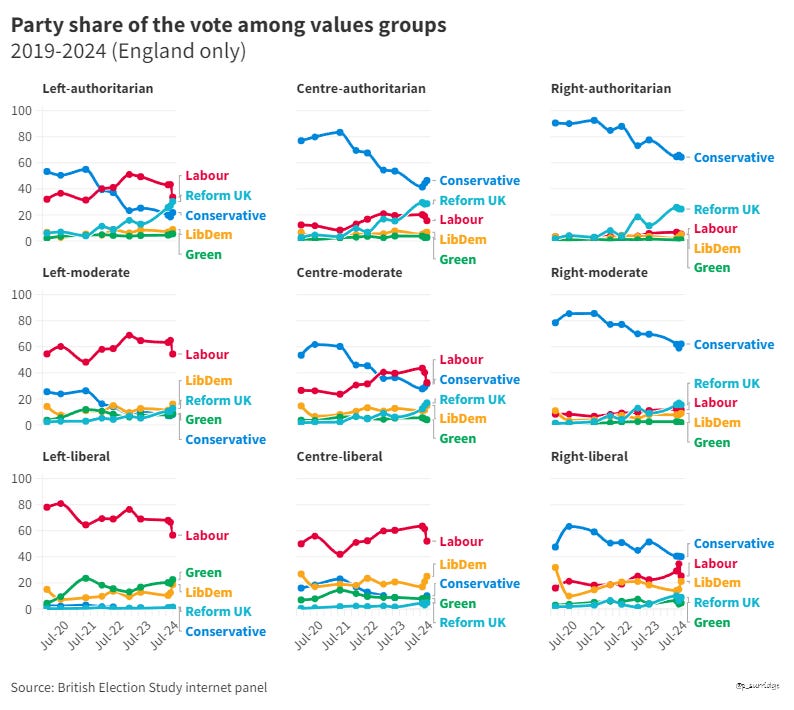

The release of the campaign and post-election waves of the British Election Study Internet Panel means there are lots of fresh analysis we can do of voters, values and preferences. This post starts with the most straightford of these, a look at how the nine values groups set out here changed in their voting preferences over the period - a period which included Covid, leaving the EU, partygate, the Ukraine War, the Israel-Palestine war, three Prime Ministers and the death of the monarch.

As set out in my previous post we would not expect values themselves to shift over such a short period (though certainly some of the events above could lead to longer term value change) but as lenses through which such events are filtered and understood we might expect some groups to change preferences in response to different events.

For this analysis I have restricted the data to England only, as the presence of additional parties in Scotland and Wales complicates the story further. I have also excluded throughout the undecided and those who said they would not vote - watch out for posts specifically on these in the coming weeks.

It is again worth stressing that these are not equally sized groups (as shown below) and critically the larger groups such as the left-authoritarians and the centre-moderates saw Labour over take the Conservatives mid-way through the parliament.

Different groups seem to shift at different times. Labour’s strategy throughout was to focus on key voter groups and not to target those in groups where they were already significantly ahead. We can see that the Green party share among the Liberal-left group rises between 2020 and 2021particularly.

Reform UK’s rise among the less liberal leaning groups comes later in the parliament, and particularly between May 2023 and May 2024. Before the return of Farage to the leadership, the party were already beginning to climb (perhaps in response to the rise of immigration up the issue agenda for some groups of voters).

The Liberal Democrats were often overlooked in the polling and commentary on the 2019-2024 parliament. And it is perhaps clear why when looking at this chart - there are no distinctive LibDem ‘bumps’ in the chart. But if we zoom into the campaign period a different picture emerges.

From the start of the campaign in late May to polling day, the Labour party lose votes, particularly among groups they had strong leads. This seems to have been mostly to the benefit of the Liberal Democrats - perhaps in the form of tactical voting - among the most liberal groups.

There are also upticks in the Conservative share. Most notably among the voters in the ‘centre’ economically but without liberal social values.

Critical of course to the outcome is where these voters were located and in what types of party contest they cast their votes. This will take a little longer to disentangle and for some questions we will have to rely on other types of data (it is difficult to understand the impact of independent candidates in individual seats with a national survey for example).

While the psephological community (people interested in elections and voters) continue to understand the election we have just had, beware of simple accounts of when and how the election was won (and lost) and especially of what might come next.