Broken coalitions: 2019 voters in value space

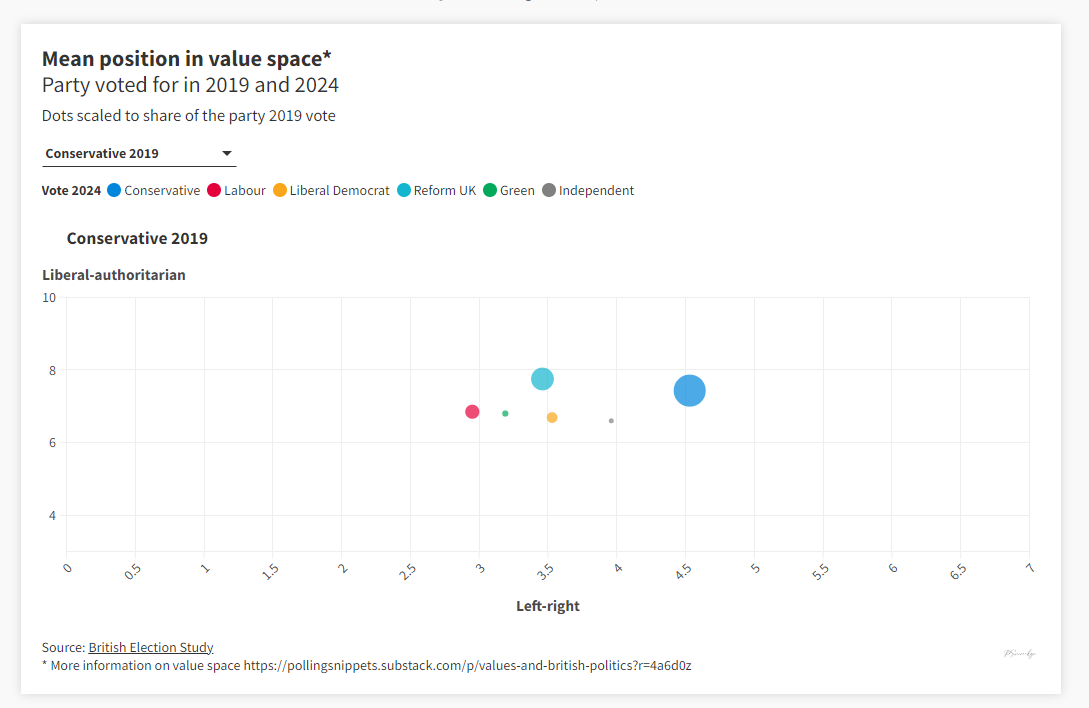

How voter groups defined by 2019 and 2024 vote fit in two-dimensional value space.

This post looks at the value positions of those who voted for the Conservatives and Labour in 2019 according to how they voted in 2024. An interactive version of the charts which also include flows for the Liberal Democrats and the Green party can be found here.

In an earlier post I set out how the two value dimensions of left-right and liberal-authoritarian can be used to creat a ‘value space’ where we can look at the average position (centre of gravity if you prefer) of different groups of voters.

In this post I take each set of party voters in 2019 and split by how they voted in 2024 to see which types of voter each party were losing from their voting coalition. Even after the 2019 election it was clear that the coalition of voters the Conservative party had brought together was going to be difficult to maintain. United around the ‘Get Brexit Done’ slogan this included those with ‘left-authorian’ values as well as right-wing liberals.

However, the Conservative party made that task even more difficult with a series shocks to the electorate, writing even before the partygate story broke I identified how being seen to operate with ‘one rule for us’ was a turnoff for their ‘new’ voters

The later impact of the Truss mini-budget then further undermined this coalition by challenging the perception of the Conservatives being competenet stewards of the economy. The result was a ‘Crumbling coalition’ of Conservative voters.

In these charts the points are scaled to show the size of the groups as a percentage of the party’s 2019 support. The Reform UK point is half the size of the Conservative point (52% of the 2019 Conservative voters also voted Conservative in 2024, 26% for Reform UK).

The most striking pattern is that every group of ‘lost’ voters are to the left of those who voted Conservative on key economic issues - in fact although statistically not distinguishable the mean for those who switched to Reform UK is slightly to the economic left of those who switched to the Liberal Democrats. Those who switched to Labour, the Liberal Democrats or the Green party are more liberal than those who stayed with the Conservatives, while those lost to Reform UK are a little more towards the authoritarian end of the scale.

At the Conservative party conference key figures, including some of the would-be leaders, have suggested that the party must save voters from an enlarged state. Yet the voters they lost are more likely to be in favour of state intervention than those they retained. Likewise, they have suggested the way to win back voters (even young voters) is to ‘win a culture war’. While there is evidence the voters that switched to Reform UK may be more enthused by this - it would at the same time likely lead to further losses (and no regains) from the Liberal Democrats.

The remains the key challenge for the party - even if the preferred strategy is to win back those who have switched to Reform UK - there seems to be some misunderstanding of these voters. Their overwhelming priority is immigration - but they are not instinctively ‘small state’ in the way the Conservative party assume. Chasing that vote with a focus on anything other than migration seems unlikely to succeed and in opposition it is difficult to see what the Conservatives can do or say on immigration that Reform UK can’t also say (and likely in ways with greater resonance).

But the other key danger is that moving ‘towards’ the perceived position of those voters, further alienates those who moved to Labour and the Liberal Democrats both of which are critical to any rebuilding of the Conservative electoral fortunes. It may make it easier for the Labour government to hold onto the ‘hero’ voters it won from the Conservatives if the Conservatives focus on issues that are not a priority for those groups (the cost of living and the NHS being the key priorities), and if they adopt positions some distance from their core values (which are both more left-wing and more liberal than the average Conservative voter).

While the Conservatives may make the task of holding onto switchers easier for the government, Labour are not without their own challenges. The election saw multi-party competition everywhere - almost every voter had at least five choices on their ballot papers. While the Labour party retained a great proportion of their 2019 vote, there were nonetheless critical groups of switchers away from the party, particularly to the Green party and to the Liberal Democrats (in many cases as tactical votes).

Despite winning seats there is only a small percentage of the 2019 Labour vote that switched to an independent candidate (reflecting that this was concentrated in a small number of seats). However, it is interesting to note that those who did switch from Labour to an independent candidate were less liberal than those who stayed with Labour, those who switched to the Liberal Democrats and those who switched to the Green party.

Those that switched to the Liberal Democrats were a more liberal than those who stayed with Labour (and a little more left-wing economically). However, the voters Labour lost to the Greens were substantially more left-wing and more liberal than the other groups. As shown here, Green party support is strongest among the liberal-left group, and there was a move from Labour to the Green party relatively early in the 2019-2024 parliament at around the time Jeremy Corbyn had the Labour whip removed. For Labour, the challenge is to understand whether an appeal to these voters on their personal values and priorities might be able to win them back or if there are particular loyalties to the former Labour leader.

The 2024 election was without doubt a verdict on the competence of the Conservative government. But the underlying fragmentation of the electorate, evident in 2015 was revealed as they struggled to maintain a coalition that had little in common in terms of their underlying values and priorities. This fragmentation poses challenges (and opportunities) for parties.

The Conservatives appear unable to grasp the reality of an electorate who despite having returned them to power repeatedly since 2015 do not currently share their values or priorities in the post-Brexit, post-Covid landscape. Meanwhile for Labour the challenge is to reconnect with the voters it was willing to sideline to win an election. Both face challenges from smaller parties who are not seeking to put together such broad coalitions and therefore are more able to connect on key values and issues in ways that are difficult for those seeking a broader base to counter effectively.

It is of course very early days in the parliament, and with different challenges to wrangle with in Scotland and Wales. More than ever though it is critical for parties (and political commentators) to move beyond two-party, one-dimensional thinking about the electorate.